Shortly before Phillipa Fallon’s first movie, The Girl In The Kremlin, was released in late April of 1957, her marriage to Bill Manhoff broke up. The court paperwork documenting their legal separation dated April 15, 1957 coldly presents the duration of their union: 12 years, 6 months, 17 days.

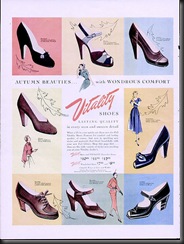

According to Leonard Grainger, Bill was “always broke” because “she liked to spend his money…She had a closet full of shoes. She loved shoes.” Grainger, Bill’s best friend, added that Phillipa was “reclusive and not too warm… [but] very stylish.”

Thayer Culver, Bill’s secretary in the 1950s, told CONELRAD that her boss “coddled” Phillipa and that he was “spellbound by her.” She added that “he was blind to what she really was.” Culver echoed Grainger’s description of Phillipa as being “reclusive,” saying that “There was a chaise in the bedroom near the fireplace and that’s where she would lounge. The room was very draped and dim.”

Contrary to some of the preceding statements, the Manhoffs’ relationship was not all one-sided. Their daughter told CONERAD that Phillipa had a high regard for her husband’s talent and once told him that he was a better writer than F. Scott Fitzgerald. Bill considered the compliment quite undeserved and Phillipa responded by giving him a Fitzgerald book as a gift with an inscription repeating her literary assessment.

According to Culver, Bill eventually adjusted to losing Phillipa by going into therapy. “He finally discovered he did not have to take care of her.”

The final judgment of divorce was issued in Los Angeles Superior Court on December 21, 1959. By this time Bill had moved on psychologically and romantically from Phillipa. Indeed, a week and one day after the final divorce decree, he married Joy Reynolds in Beverly Hills (this union last until 1967). Joy told CONELRAD that Bill never really spoke about Phillipa, but that she was aware of the unusual diet practices of his former family. She added that she knew, for example, that Bill had decided to treat his diabetes not with traditional medicines, but rather through an alternative diet. It was early in their marriage, according to Joy, when Bill decided to stop being a vegetarian. “The first thing he wanted to eat was bacon!”

When asked if his friend ever talked about Phillipa after the divorce, Leonard Grainger told CONELRAD “No, he never looked back.” But Bill did pay monthly alimony and child support which kept him tethered to his former wife for many years.

The largest outstanding expense to be found in the Manhoffs’ divorce paperwork (which was found on microfilm in the basement of the Los Angeles Department of Public Records) is for $2,000 owed by Phillipa to Dr. E. Paul Bindrim. Bindrim was an analyst Phillipa saw during the period that preceded her separation from Bill. And not unlike the other “guru” figures that populate Phillipa’s life, Bindrim was a strange character with questionable methods. His 12-hour private therapy sessions, according to the Manhoffs’ daughter, put a considerable strain on her parents’ marriage. The daughter, who once met the therapist, told CONELRAD that he made her feel uneasy. At the time of these costly and probably harmful sessions, Bindrim was not even a licensed psychologist. An October 12, 1956 Pasadena Star-News item refers to him as a “psychic expert” and “telepathist” who was scheduled to give a lecture on how “the average person can develop the good luck and good judgment that marks the lives of successful men and women.”

Edward Paul Bindrim was born in New York in 1920 and earned his bachelor’s degree from Columbia University and his master’s degree from Duke University. At Duke he performed research in parapsychology. In 1958 he was ordained in the Church of Divine Metaphysics and became a minister of the Church of Religious Science in Glendale, California. He finally obtained his psychology license in 1967, the same year he held his first “nude workshop” in Deer Park, CA. He went on to become famous for being the father of nude psychotherapy. The January 8, 1998 obituary for Bindrim in the Los Angeles Times characterized his practice as consisting of “placing several people in [a] warm pool for long sessions of touching and massaging, talking and sometimes shouting or acting out rage.” The Times stated that Bindrim called these sessions “nude marathons” or “Aqua-energetics.”

The exact nature of Phillipa’s therapy with Bindrim in the 1950s is not known, but Dr. Ian Nicholson, an academic who has written about Bindrim and who was consulted by CONELRAD, said it might have had something to do with the “power of positive thinking.” The Church of Religious Science, of which Bindrim was associated, promoted this philosophy. As seen in the Star-News item to the right, however, Bindrim was trading on his paranormal / ESP research around the same time that he was treating Phillipa. Dr. Nicholson summed things up by telling us that based on what he knew about this controversial therapist, he believed Bindrim was “prepared to consider almost anything that resonated with his clients.”

Phillipa’s subsequent therapists, Dr. Lawrence F. Barker and Dr. Maurice Walsh, were apparently of the more traditional school (although Walsh achieved some degree of notoriety for diagnosing Nazi war criminal Rudolph Hess with latent schizophrenia in 1948).

Another fascinating detail revealed in the Manhoffs’ divorce paperwork is a reference to her ill-fated play, The Kissing Man. In the settlement agreement, Bill Manhoff is given a generous “one half of one percent” of “any and all income or economic gain derived from the sale or production of the musical comedy…” Not surprisingly, CONELRAD was unable to find a copy of The Kissing Man, though we did check the copyright office at the Library of Congress. We found other works copyrighted by Phillipa, but not this particular item. There will be more on the other copyrighted material in later posts.

The divorce documents suggest that Phillipa liked to write because there is a reference to “three scripts written by the wife under the name Phillipa Strange.” The mind reels at the possibilities. Alas, we checked the Writers Guild of America and the Library of Congress under all of Phillipa’s many aliases and we could find no trace of these screenplays.

From the time of the separation in 1957 through the final divorce and beyond, Phillipa and her daughter (custody was awarded to her with visitation rights granted to Bill) lived at Tower. They moved to a much smaller house on Stradella Court in Bel Air in 1962, but at the time Phillipa won her most famous role as a beatnik in High School Confidential!, she was still residing in a 16-room mansion.

No comments:

Post a Comment